March 18th, 2020

Albert Einstein made many contributions to physics, but the only one that most people are aware of is his theory of Special Relativity. This is one with the weird conclusions about spatial contraction and time dilation. It assumes that the speed of light is an absolute constant. For example, consider these three experimenters:

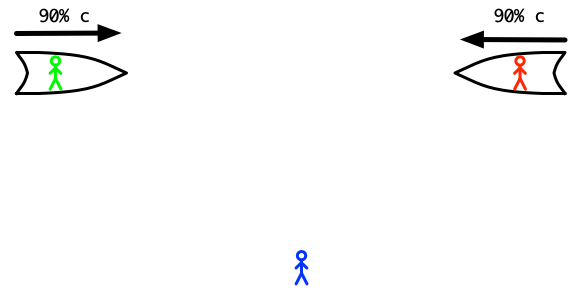

Blue Guy clocks Green Guy going 90% of the speed of light to the right; he also clocks Red Guy going at 90% of the speed of light to the left. Therefore, Green Guy must see Red Guy approaching him at 180% of the speed of light. Right?

Wrong! Einstein figured that, if the speed of light had to be the same for everybody, then somehow Green Guy and Red Guy would have to undergo changes in their spatial and temporal measurements to get things to come out correctly. In other words, their yardsticks would have to shorten and their clocks would have to slow down. Einstein worked through all the mathematics of this and came up with his equations for how this would work. Along the way, he also figured that their masses would have to increase in proportion to their speed. This is what led to the famous equation E = mc2.

Michelson and Morely screw up everything

Now, this all sounds crazy, and physicists would have dismissed it all as utter nonsense if it weren’t for two American physicists, Albert Michelson and Edward Morley, working at a small college in Ohio. They were working to measure the ‘luminiferous aether’.

Huh?

This takes us back to the greatest physicist you never heard of, James Clerk Maxwell. This was a Scottish physicist who in 1865 put together what was known about the laws of electricity and magnetism and showed that light is really just a wave of interacting electric and magnetic fields. A changing electric field generates a changing magnetic field next to it, which turns around and generates a changing electric field next to it, and so on, with the resulting wave propagating through space. It was an absolutely brilliant synthesis of different fields of physics (electricity and magnetism) to produce the astounding result that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon. Everybody was awestruck and Maxwell’s equations for electromagnetic waves (light) were quickly embraced. They even provided a way of calculating the speed of light from measurements of electric and magnetic fields.

This was all very heady stuff and physicists were very smug about having solved so much. But there was one little nagging question: what did light move through? After all, you can’t have an ocean wave without water. You can’t have a sound wave without air. A wave needs a ‘medium’ through which it must propagate. So what was the medium through which light propagated?

Physicists came up with a name for this medium: ‘luminiferous aether’. That sounds really scientific, doesn’t it? This had to be some sort of invisible stuff that permeated the universe, providing the carrier for light. So all the physicists had to do was find the luminiferous aether.

But no matter how hard they looked, they couldn’t find it. In 1887, Michelson and Morley came up with a very clever scheme for getting partway there: they would measure the speed with which the earth is moving through the luminiferous aether. After all, since the earth is going in a circular orbit, it will be going in opposite directions on opposite sides of its orbit. So all they had to do was measure the speed of light very, very accurately on two occasions six months apart. They figured out a clever scheme for doing so and carried out their measurements. The result they got was disastrous: there was no difference! The results they got at different times of the year showed no change at all, even though the earth was moving in opposite directions.

This result was so baffling that at first physicists couldn’t accept it. So other physicists built their own instruments and repeated the experiment, and got the same results. They tried all sorts of variations, but always got the same result.

The walls close in

For the next 18 years physicists struggled to escape the conundrum that Michelson and Morley had created. They tried different experiments—it didn’t help. They came up with all sorts of lame excuses for why Michelson and Morley had to be wrong—nobody believed them. In the early years after the experiment, physicists were confident that they could fix the problem, but the years rolled by and no solution appeared.

By 1905, physicists were desperate. Maxwell’s beautiful system of electromagnetism was undermined by that damned Michelson-Morley experiment, and there wasn’t anything they could do to save Maxwell’s equations.

That’s the only reason why anybody took seriously Albert Einstein’s crazy proposals that space and time were variable. The more they poked around with Einstein’s equations, the more they realized that Einstein’s stuff actually worked. It was insane—but it worked.

Had Einstein published his proposal ten years earlier, physicists would not have been desperate enough to take him seriously. They would have dismissed his kooky ideas with wild laughter, and we would never have heard of Albert Einstein.

Thus, the intellectual atmosphere was just as important to Einstein’s success as the fact that he was right.